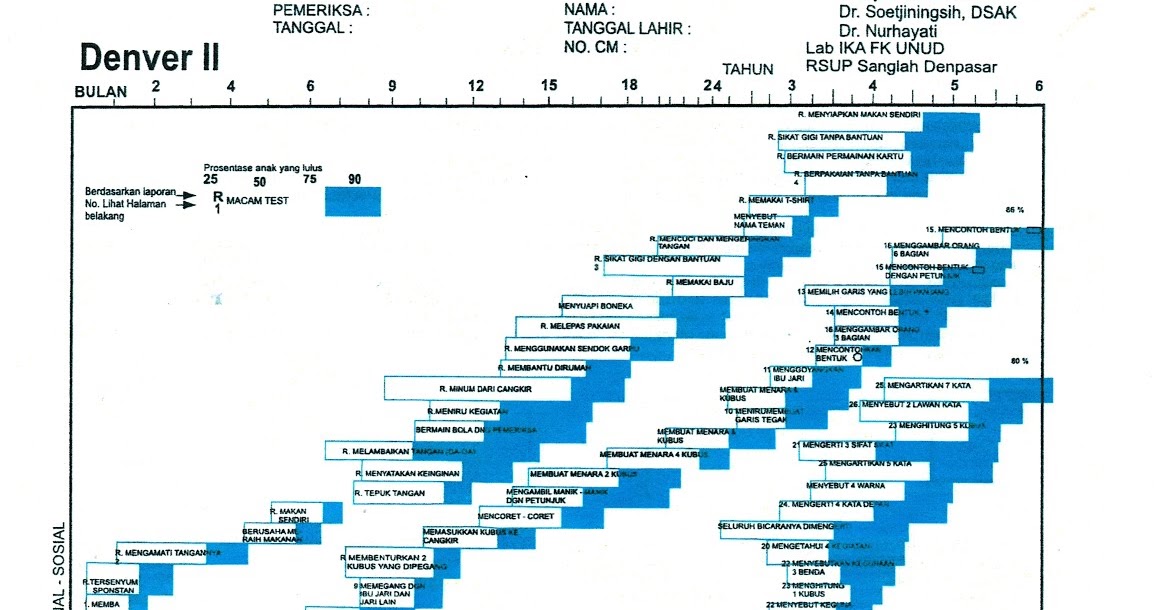

She was proud that she was chosen for this assessment, and told her sisters that she was special for being selected. I began the assessment with the Personal – Social section of the exam and according to her mother’s report S.G. was capable of performing all the tasks except preparing cereal. S.G.’s mother informed me that although she is able to pour the cereal in a bowl, she does not allow her daughter to pour the milk due to concerns of making a mess. As I was interviewing the mother regarding S.G.’s abilities, she would also chime in, and inform me that she can do all the things I asked, and even offered to demonstrate. S.G. expressed her love for her favorite board games Hungry Hungry Hippo and Ants in the Pants, which she loves to play with her best friends and sisters. S.G. successfully passed at least three items to the left of the age line, and all the tasks in the boxes the line fell through. Because she passed we moved on to the Fine Motor – Adaptive…show more content…

enjoyed her experience. Because she knows me personally I found it very easy to talk to her, and she had no difficulty engaging in conversation with me. S.G. failed two tasks; defining seven words in the Language category, and balancing on each foot for 4, 5 and 6 seconds. The chronological age line does not fall through the blue part of the bar for those specific tasks, and therefore it is not concerning. Although she did not succeed in completing these two tasks, today’s Denver Developmental Screening Test was normal. It was a pleasure performing this test on S.G. and, if given the chance to reassess her I would perform the exam in a more private setting, away from all the distractions so that she may be able focus solely on the exam. According to beststart.org’s “On Track Guide” as far as development by age and domain is concerned S.G. accomplishes the skills listed for children her age

- Jul 13, 2018 Includes: ASQ (Ages and Stages Questionnaire), Denver Developmental Screening Test II (DDST-II), Early Screening Inventory-Revised (ESI-R), IDA (Infant Toddler Developmental Assessment), HELP (Hawaii Early Learning Profile), Carolina Curriculum for Infants and Toddlers, AEPS (Assessment Evaluation & Programming System), PLS (Preschool Language Scale), Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test, Rossetti Infant-Toddler Language Scale, and Batelle Developmental Inventory.

- These images are a random sampling from a Bing search on the term 'Denver Developmental Screening Test II.' Click on the image (or right click) to open the source website in a new browser window.

See full list on ukessays.com.

| Denver Developmental Screening Tests | |

|---|---|

| Purpose | identify young children with developmental issues |

The Denver Developmental Screening Test was introduced in 1967 to identify young children, up to age six, with developmental problems. A revised version, Denver II, was released in 1992 to provide needed improvements. The purpose of the tests is to identify young children with developmental problems so that they can be referred for help.

The tests address four domains of child development: personal-social (for example, waves bye-bye), fine motor and adaptive (puts block in cup), language (combines words), and gross motor (hops). They are meant to be used by medical assistants or other trained workers in programs serving children. Both tests differ from other common developmental screening tests in that the examiner directly tests the child. This is a strength if parents communicate poorly or are poor observers or reporters. Other tools, for example the Age and Stages Questionnaires, depend on parent report.

Denver Developmental Screening Test[edit]

The test was developed in Denver, Colorado, by Frankenburg and Dodds.[1] As the first tool used for developmental screening in normal situations like pediatric well-child care, the test became widely known and was used in 54 countries and standardized in 15.[2] The Denver Developmental Screening Test was published in 1967. During its first 25 years of use, one study found it to be insensitive to language delays.[3] Other concerns arose: that norms might vary by ethnic group or mother's education, that norms might have changed, and that users needed training.[citation needed]

The Denver Developmental Screening Test

Denver II[edit]

Research basis[edit]

The Denver Developmental Screening Test was revised in order to increase its detection of language delays, replace items found difficult to use, and address the other concerns listed.[4] There are 125 items over the age range from birth to six years. An examiner administers the age-appropriate items to the child, although some can be passed by parental report. Each item is scored as pass, fail, or refused. Items that can be completed by 75%-90% of children but are failed are called cautions; those that can be completed by 90% of children but are failed are called delays. A normal score means no delay in any domain and no more than one caution; a suspect score means one or more delays or two or more cautions; a score of untestable means enough refused items that the score would be suspect if they had been delays. The Denver II is available in English and Spanish. Videotapes and two manuals describe 14 hours of structured instruction and recommend testing a dozen children for practice. Beyond this a professional degree is not required. As with all developmental testing, one must follow the instructions in detail.[citation needed]

Denver Developmental Screening Test Example

The standardization sample of 2,096 children was selected to represent the children of the state of Colorado. The test has been criticized because that population is slightly different from that of the U.S. as a whole. However, the authors found no clinically significant differences when results were weighted to reflect the distribution of demographic factors in the whole U.S. population. Significant differences were defined as differences of more than 10% in the age at which 90% of children could perform any given item.[5] Separate norms were provided for the 16 items whose scores varied by race, maternal education, or rural-urban residence.[citation needed]

Interpretation[edit]

The author of the test, William K. Frankenburg, likened it to a growth chart of height and weight and encouraged users to consider factors other than test results in working with an individual child. Such factors could include the parents’ education and opinions, the child’s health, family history, and available services. Frankenburg did not recommend criteria for referral; rather, he recommended that screening programs and communities review their results and decide whether they are satisfied. [6]

In 2006 the American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Children with Disabilities; Section on Developmental Behavioral Pediatrics published a list of screening tests for clinicians to consider when selecting a test to use in their practice. This list includes Denver II among its choices.[7] The chairman of the committee wrote: “In the practice of developmental screening and surveillance, we recommend the incorporation of parent-completed questionnaires or directly administered screening tests into the process of surveillance and screening. However, their results should be combined with attention to parental concerns and the pediatrician’s opinion, rather than replacing them, to augment the screening process and increase identification of children with developmental disorders”.[8]

Studies in practice[edit]

One study evaluated the Denver II in terms of how its results matched those of a psychologist in five child-care centers: two serving the children of college-educated white parents and three serving low-income African-American children. The psychologist evaluated 104 children, of whom 18 were judged to be delayed [9]). All but two of the 18 came from the low-income centers but no mention is made regarding use of separate norms for African-American children. Results of the Denver II, using an older scoring method, included 33% questionable tests, in between normal and abnormal. If their scores were considered normal, too many children with delays would be missed (low sensitivity); if their scores were considered abnormal, too many children would be referred (low specificity). On the basis of this study, the Denver II fell into disfavor, and it is now seldom mentioned in reviews. Materials may no longer be purchased in hard copy, but they are available at no charge.[citation needed]

Another study evaluated the Denver II in the screening program of a community health center.[10] Here the criterion for abnormality was the eligibility of children for Early Intervention, according to the judgment of speech-language pathologists and other professionals in two suburban school districts. This study included 418 children in all and 64 who needed EI. The success of the screening program was judged in terms of predictive value: the probability that a child, if referred, would be eligible for services. The predictive value was 56%; allowing for children who were referred but not evaluated, it was 72%; this compared favorably with two studies using the Ages and Stages Questionnaire in clinics, which found comparable predictive values of 50% and 38%.[11] The study showed the value of taking into account other information besides the test result because the screener increased the predictive value from 44% to 56% by using her judgment not to refer some children with minor delays.

In a study of two-stage screening, children were prescreened with Frankenburg’s Revised Prescreening Developmental Questionnaire[12] and 421 with suspect scores were given the Denver II and evaluated by independent examiners.[13] In children under 18 months the prevalence of abnormality was 0.19 on diagnostic tests, and the Denver II had a positive predictive value of 0.36, a negative predictive value of 0.90, a sensitivity of 0.67, and a specificity of 0.72. The authors concluded that a suspect Denver II “should lead to careful monitoring and rescreening unless provider or parental concern suggests the need for immediate referral.” Among children 18–72 months old, the prevalence of abnormality was 0.43, the positive predictive value was 0.77, the negative predictive value was 0.89, the sensitivity was 0.86, and the specificity was 0.81. The authors concluded that in their program a suspect Denver II should usually result in a referral. (Positive predictive value meant the probability that a child with a suspect Denver II would be diagnosed as abnormal when evaluated; negative predictive value meant the probability that a child with a normal Denver II would be diagnosed as normal when evaluated.)[citation needed]

A study of 3389 children under five in Brazil has produced a continuous measure of child development for population studies.[14] The measure was based on the Denver Developmental Screening Test but can be used with the Denver II.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^Frankenburg, W.K. (1967). 'The Denver Developmental Screening Test'. The Journal of Pediatrics. 71 (2): 181–191. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(67)80070-2. PMID6029467.

- ^Frankenburg, W.K.; Dodds, J.; Archer, P. (1990). Denver II Technical Manual. Denver Developmental Materials, Inc. p. 1.

- ^Borowitz, K.C.; Glascoe, F.P. (1986). 'Sensitivity of the Denver Developmental Screening Test in Speech and Language Screening'. Pediatrics. 78 (6): 1075–1078. PMID3786032.

- ^Frankenburg, W.K.; Dodds, J.; Archer, P. (1990). Denver II Technical Manual. Denver Developmental Materials, Inc. p. 1.

- ^Frankenburg, W.K.; Dodds, J.; Archer, P. (1990). Denver II Technical Manual. Denver Developmental Materials, Inc. p. 6,18–19.

- ^Frankenburg, W.K.; Dodds, J.; Archer, P. (1990). Denver II Technical Manual. Denver Developmental Materials, Inc. p. 20–22.

- ^American Academy of Pediatrics, Council on Children with Disabilities; Section on Developmental Behavioral Pediatrics; Bright Futures Steering Committee; Medical Home Initiatives for Children with Special Needs Project Advisory Committee. Identifying infants and young children with developmental disorders in the medical home: an algorithm for developmental surveillance and screening. Pediatrics, 2006;118:405–420

- ^Lipkin, P.H.; Gwynn, H. (2007). 'Improving developmental screening: Combining parent and pediatrician opinions with standardized questionnaires'. Pediatrics. 119 (3): 655–56. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-3529. PMID17332228. S2CID33274155.

- ^Glascoe, F.P.; Byrne, K.E.; Ashford, L.G. (1992). 'Accuracy of the Denver II in developmental screening'. Pediatrics. 89 (6 Pt 2): 1221–1225. PMID1375732.

- ^Dawson, P.; Camp, B.W. (2014). 'Evaluating developmental screening in clinical practice'. SAGE Open Medicine. 2: 205031211456257. doi:10.1177/2050312114562579. PMC4712749. PMID26770755.

- ^Guevara, J.P.; Gerdes, M.; Localio, R. (2013). 'Effectiveness of developmental screening in an urban setting'. Pediatrics. 131 (1): 30–37. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-0765. PMID23248223. S2CID16427065.

- ^Frankenburg, W.K. (1987). 'Revision of the Denver Prescreening Questionnaire'. J. Pediatr. 110 (4): 653–57. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(87)80573-5. PMID2435879.

- ^Burgess, D.; Camp, B.W.; Spicer, C. (1996). 'Accuracy of the Denver II in a clinical developmental screening protocol'. Abstract Presented at the Society for Developmental-Behavioral Pediatrics. doi:10.1097/00004703-199608000-00029.

- ^De Lourdes Drachler, M.; Marshall, T.; de Carvalho Leite, J.C. (2007). 'A continuous-scale measure of child development for population-based epidemiological surveys: A preliminary study using item-response theory for the Denver test'. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology. 21 (2): 138–153. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3016.2007.00787.x. PMID17302643.

Copy Of Denver Development Test

External links[edit]

- Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics at American Academy of Pediatrics

- HealthyChildren.org American Academy of Pediatrics